Entering 2020, the cruise industry had been a standout performer within the travel and leisure sector. Expanding beyond its traditionally loyal customer base, global passenger numbers grew from 17.6 million in 2009 to 29.7 million in 2019, a 69% increase. Capacity also increased, with the global supply of passenger bed days increasing 40.6% from 2014 to 2019.[1]

The lion’s share of this growth was generated by the sector’s three major companies, Carnival Corporation & Plc (CCL), Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) and Royal Caribbean Group (RCL). Of the 323 cruise ships estimated to be in operation in 2021, these major players account for 176. Leading into the pandemic, their collective market capitalisation was $75.8 billion, with total revenues of approximately $38 billion. By comparison, the next six largest cruise operators reported aggregate total revenues of approximately $10 billion.[2]

While being one of the biggest benefactors of the boom in tourism since the financial crises, the cruise industry has also been one of the most impacted by the pandemic. This article examines this impact, as well as the actions that have been taken to withstand the sustained shut down in operations. What is now becoming increasingly clear is that although actions taken to shore up the balance sheet were necessary and vital to the survival of many, the impact of these actions will continue to be felt well after cruising has resumed.

A COVID collapse and scramble for cash

On 20 February 2020, the cruise industry's previously spectacular growth came to a grinding halt with the World Health Organisation (WHO) announcing that half of all COVID-19 cases outside of China were among the passengers of Carnival’s Diamond Princess.[3] Of the 712 passengers on board, 13 died due to COVID-19.[4]

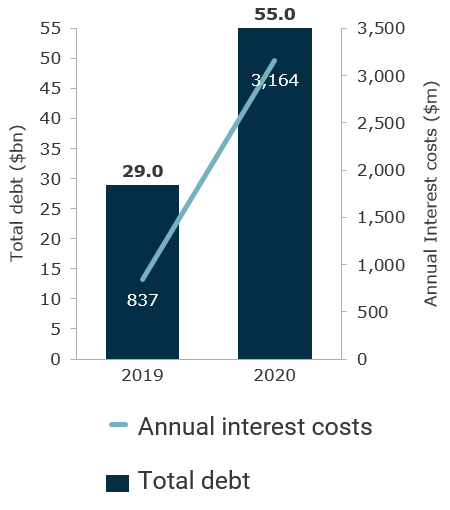

“Floating petri-dish” became the buzzword for cruise liners and port authorities as the world suspended vessel arrivals. In March 2020, the United States Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a no-sail order, suspending all cruises in the US, while the main industry body, Cruise Lines International Association, also voluntarily suspended all operations. With close to zero revenues for the majority of the year, a scramble for cash ensued as operators were faced with meeting existing cash outlays, as well as the prospect for further costs associated with enhanced sanitation and testing requirements.[5] RCL alone reported an average monthly cash burn rate of between $250m - $290m for 2020.[6] By the end of Q1 2021, through a combination of debt and equity, a total of $43.4 billion in liquidity had been raised by the sector’s three major players to help weather the storm.[7]

A much-changed on-board experience post-pandemic

As the world emerges from the pandemic, it is becoming increasingly clear that the initial voyages will be very different to those of 2019. The UK’s first cruise since the pandemic departed in late May carrying only 1,000 of its 6,334 passenger capacity. The four-night cruise, with a stop in Portsmouth, was limited to British residents, with all passengers being tested for COVID-19 before departure. Passengers will also be required to be tested mid-week on seven-day cruises.

Further afield, RCL and Genting Cruise Lines have been offering “cruises to nowhere” for residents of Singapore. These cruises have no stops, simply departing and arriving back at the same port after a few days sailing. The vessels operate with reduced capacity and social distancing measures are also in place.[8]

How have heads been kept above water?

With reduced capacity and a marked increase in leverage, many are wondering how long it will take the industry to get back to breakeven levels, or indeed what these new breakeven levels are, given the debt mountains that need to be serviced. Operational breakeven points may have improved given cost efficiencies achieved during lockdown but free cash flow breakeven points will have moved significantly in the other direction.

For many operators, achieving operational cash flow breakeven levels does not necessarily mean returning to full occupancy. CCL, for instance, reports that it can get back to better than cash flow breakeven levels for its vessels with just 30%-50% occupancy. Full operations and occupancy for the top 25 vessels in the company’s fleet generates sufficient cash flow to cover the shutdown costs of the rest of the fleet and the company’s full SG&A expense.[9]

Despite the big players being able to subsidise the operational costs of idle ships with relatively few larger ships, there are additional overheads which will continue to burn mountains of cash and cause headaches for management. Not least is the eye-watering increase in debt accrued across the industry. CCL, NCL and RCL have increased their interest costs by 8.7x, 2.0x and 2.7x respectively.

Our analysis suggests that the impact of the new, additionally levered capital structures is not insignificant. We expect that each of the main players will need to return to at least 87% of pre-COVID-19 revenue before cash burn is completely halted. Each of the three companies have significant debt maturity events before the end of FY22, whilst Carnival even has debt repayments to make in Q2 FY21. The sooner business returns to normal, the better placed they will be to navigate those maturity events.

Our analysis suggests that the impact of the new, additionally levered capital structures is not insignificant. We expect that each of the main players will need to return to at least 87% of pre-COVID-19 revenue before cash burn is completely halted. Each of the three companies have significant debt maturity events before the end of FY22, whilst Carnival even has debt repayments to make in Q2 FY21. The sooner business returns to normal, the better placed they will be to navigate those maturity events.

In addition, operators will need to adapt their business models to deal with the near term realisation that customers are unlikely to book months in advance, putting down substantial deposits, to a situation where customers may leave booking to the last minute due to continuing COVID-19 uncertainty. The impact this will have in working capital will need to be understood by all operators.

Stay ship-shape on cost reductions, with an uncertain future ahead

As the world starts to reopen following the COVID-19 pandemic, the cruise sector is one that will feel the effects for some time to come. Huge mountains of debt raised to keep the industry afloat will eventually need to be repaid and a return to 2019 occupancy levels will be a minimum requirement for many. Cost reduction efforts made during the pandemic will need to be sustained through the reopening, with discounting kept to a minimum. Although initial signs are that bookings are strong for 2022, the industry will need to lean heavily on its loyal customer base to ensure a return to profitability and the pre-pandemic growth years.

-----------------------

[1] CLIA - The Economic Contribution of the International Cruise Industry Globally in 2019. Passenger bed days are defined as the number of berths available times the number of days cruising.

[2] https://cruisemarketwatch.com/capacity/ and company annual reports.

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2020/feb/20/coronavirus-live-updates-diamond-princess-cruise-ship-japan-deaths-latest-news-china-infections

[4] John Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center

[5] https://www.wsj.com/articles/cruise-lines-budget-for-extra-costs-as-they-prepare-to-restart-sailings-11621598402

[6] https://www.rclinvestor.com/content/uploads/2021/02/Royal-Caribbean-Group-Reports-on-2020-Results-and-Provides-Business-Update.pdf

[7] Company filings.

[8] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-04-01/cruises-to-nowhere-extended-as-singaporeans-seek-to-go-anywhere

[9] Carnival Plc (CCL-GB), Business Update Call, 7-April-2021 10:00 AM ET