Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has served as a catalyst to potentially strengthen the NATO alliance [1] and help meet the demands for which it was established, which is “to unite efforts for collective defense and for the preservation of peace and security.” [2]

As such, the crisis is a wake-up call for European NATO members who have signaled they can no longer afford to invest less than 2% of their GDP in their armed forces. Following the Ukraine invasion, most of these countries promptly increased defense budgets to 2% of GDP. As the crisis continues, we believe a broader increase is likely. During the Cold War, for instance, Germany spent 2.8% of GDP (1980-1990 average) on defense; France 3.1%; and UK 4.9% [3].

In our view, recent budget increases serve as a bailout of these countries’ armed forces after decades of crippling underinvestment. Over the long term, however, higher spending will position the region on a more sustainable trajectory. By allocating 2% of GDP, Germany’s budget would equal €75.5 billion in 2022, and rise to €85.6 billion in 2026 [4]. By comparison, Russia’s defense budget in 2021 was €63 billion.

Immediate Imperatives

NATO members should focus on four priorities in the short term:

- Replenish: Inventories will likely need to be replenished following the transfer of weapons and ammunition to Ukraine and the backstopping of Eastern European countries such as Poland, Slovakia, Czech Republic, or the Baltics. For example, the French army will likely need to replace 10 to 12 self-propelled Caesar howitzers, while the UK agreed to backfill the Polish T-72 tanks transferred to Ukraine by supplying Challenger 2 battle tanks.

- Resize: Military capabilities in Europe have shrunk since the Cold War ended. The past two decades have focused on counter-terrorism type conflicts. As a result, European forces do not seem appropriately sized to sustain a high intensity conflict with high attrition of equipment and personnel. Consider that after slightly more than two months of conflict, Russia lost 603 main battle tanks (including 315 destroyed), according to Oryx. As of now, Germany has only 289 main battle tanks (Leopard 2) in stock, with 183 operational. Of 51 Tiger attack helicopters, only nine are operational [5].

- Restore: Strategic gaps in capabilities of European armed forces also need to be addressed. Prior to the invasion of Ukraine, French and German armed forces were leasing the Antonov from Russian and Ukrainian companies to send their forces abroad. This is no longer sustainable. Several European countries still rely on Soviet-era systems for air and missile defense, such as Slovakia’s S300.

- Rethink: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has triggered a shift in war doctrine. The following questions need to be considered amid a reevaluation of how armed forces should operate to sustain a high-intensity conflict:

- What is the required depth and mass of armed forces needed to ensure their ability to limit impact on operations amid high attrition of equipment and personnel?

- How do you arbitrate between high-tech and low-tech equipment (“High-Low mix”) and decide on future allocation of investments and resources? For example, do you invest in developing high-tech hypersonic missiles? Or, do you invest in a swarm of low-cost drones capable of saturating enemy forces?

- What is required to conduct multi-domain military operations? This includes figuring out how to coordinate and integrate all available forces (i.e., land, air, sea, space, cyber) to leverage the entirety of firepower and regain superiority on the battlefield. Given Russia’s tactics in Ukraine, cybersecurity capabilities (both offensive and defensive) are becoming increasingly important for European armed forces to develop and demonstrate.

- How will information operations capabilities be established or improved? This requires analysis of the spectrum of capabilities needed to conduct strategic, operational, and tactical level operations to counter adversary information warfare across each domain, both on and off the battlefield.

Assessing upcoming demand

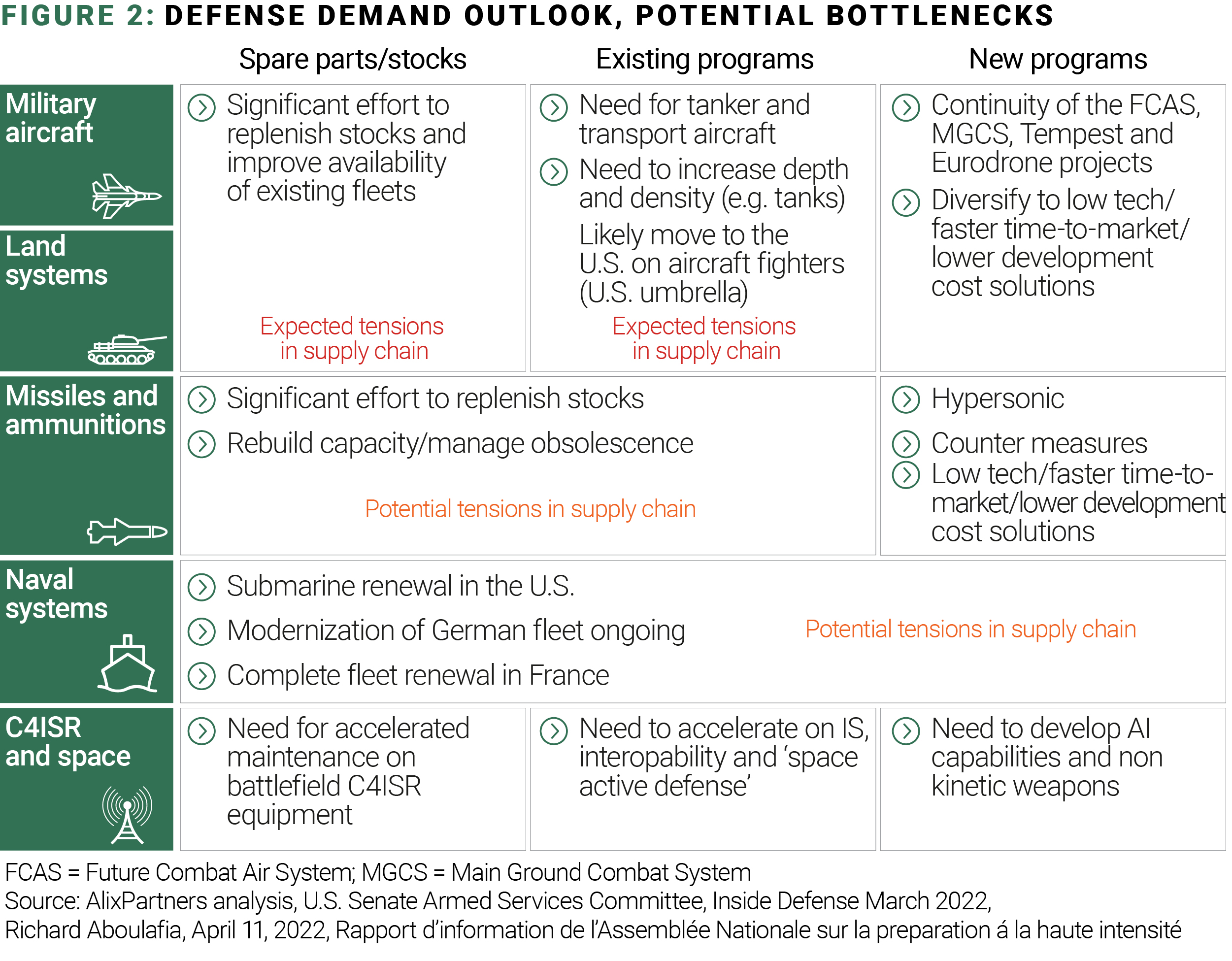

Demand on defense systems will primarily cover three domains: spare parts; existing programs; and new developmental programs. All segments – aircraft, land systems, missiles, ammunitions, naval systems, C4ISR, and space – are poised for growth.

A look at specific budgets and recent announcements helps clarify needs. In Germany, projections on how to allocate the announced €100 billion for defense provide a view of priorities for its armed forces, starting with ammunition (€20 billion), fighter aircraft (F-35, Eurofighter), and missile defense systems.

A non-exhaustive list of additional efforts needed in France include €3.5 billion to increase ammunition stock, and €2.5 billion to double equipment running hours; an increase in the number of Meteor missiles; and recommitment to the ambition of reaching a force of 300 combat aircraft.

Enablers to Success

To fulfill this upcoming demand, the following enablers are required:

- Clear objectives: Without guidance from leadership, the defense industry will likely be unable to support armed forces. Clearly expressed demand is critical, with detailed requirements (i.e., capabilities, quantities, locations, etc.) and acceptable delivery timelines.

- Production capacity: Production capacity already exists. However, for some programs that have not been in demand for a long time (e.g., Stinger missiles), capacity needs to be rebuilt and obsolescence addressed. Some capex may be required to create new production capacity and support demand. Some solutions already exist and can be used, including: “shadow” production lines; repurposing of existing production units or assembly lines to defense usage; and contracting industrial players to secure fast ramp-up on defense equipment.

- Planning and scheduling: NATO’s defense industry relies on visible, predictable, and stable requirements from armed forces. However, recent events have changed the industry operating philosophy, with speed and adaptability to a fast-changing environment as key criteria for success. As of now, many weapon systems are facing long production lead times: production of an artillery projectile -- from ordering the raw material to completion -- is estimated to vary between two and three years [6]. The production of a cannon from the French Caesar howitzer requires 18 months in total [7]. Moving forward, central planning and coordination of the production ramp-up is required.

- Supply chain readiness: Industrial defense players have recently highlighted existing limitations within the supply chain to support production ramp-up of defense systems. As highlighted by Raytheon Technologies in its recent earnings call, supply chain constraints continue to be an issue, especially on electronics with longer lead times (from three to more than 12 months) and for Raytheon Missiles & Defense with rocket motors supply delays [8]. In parallel, delivery lead times on some raw materials have increased.

- Financing: Until the invasion of Ukraine, many investors were intentionally excluding defense related assets from their investment policies. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has clearly reminded everyone that investments in defense and security are essential to the resilience and sustainability of Western democracies. But investors’ exclusionary policies have yet to be revised, particularly among international investors.

- Workforce: Europe’s defense industry employs 600,000 people [9], with a ~45-year-old median age [10]. A massive recruitment plan has been launched by all major defense companies with four challenges: scarce competencies; attractiveness of the sector with a negative image as an arms producer; higher turnover since the beginning of the COVID crisis; and a long learning curve requiring the loyalty of employees when training.

If these enablers are not met by European NATO members, solutions proposed by the US defense industry can help fill immediate needs. The recent German acquisition of 35 F-35 and 60 CH-47F Chinook heavy-lift military helicopters represents that direction. Nevertheless, while this trend may secure involvement of the US Armed Forces in case of an attack on one of the European NATO members, it is ultimately a step back for the European defense industry.

Collaboration will drive European defense integration

The ability of Europe to invest in its defense industry and restore deterrence will likely define the long-term mission and viability of the NATO alliance. A sizable risk is posed by a potential lack of coordination among all stakeholders involved in this effort. And, if each country focuses on its own industry, this historical opportunity to build and strengthen a European defense industry could be lost.

If done correctly, this moment presents an opportunity for European NATO members to leverage the alliance and the European Union on multiple fronts:

- Sharing capabilities across Europe (i.e., purchase of raw material, stock of ammunitions and missiles or spare parts)

- Jointly investing in defense and security capabilities, such as information warfare capabilities or air and missile defense on the Eastern flank of the EU

- Improving coordination or centralizing the definition of specifications and acquisition of equipment to reduce the number of European defense platforms

- Supporting the emergence of efficient low-tech defense and security solutions in Europe

- Ensure competitiveness and exportability of European defense and security solutions

For a deeper discussion about this topic, contact:

Eric Bernardini

Global Lead, Aerospace, Defense, and Aviation

[email protected]

Etienne Muselier

Director

[email protected]

_______________________

[1] https://www.npr.org/2022/05/18/1099679338/finland-and-sweden-formally-submit-nato-membership-applications

[2] The North Atlantic Treaty Washington, D.C., April 4, 1949

[3] Our World in data

[4] SIPRI “Explainer: The proposed hike in German military spending”, March 25th, 2022

[5] Bundeswehr: Keine großen Fortschritte in der materiellen Einsatzbereitschaft (esut.de), January 2022

[6] French National Assembly: information report from the National Defense and Armed Forces Commission, February 17th, 2022

[7] French National Assembly: information report from the National Defense and Armed Forces Commission, February 17th, 2022

[8] Raytheon Technologies Q1 2022 Earnings Call

[9] AlixPartners analysis, Bruegel