Yesterday’s rate decision – a 25bps increase – was welcomed by markets. Not because the increase will not be painful but because a 50bps increase would have signalled that reversing inflation is far from done.

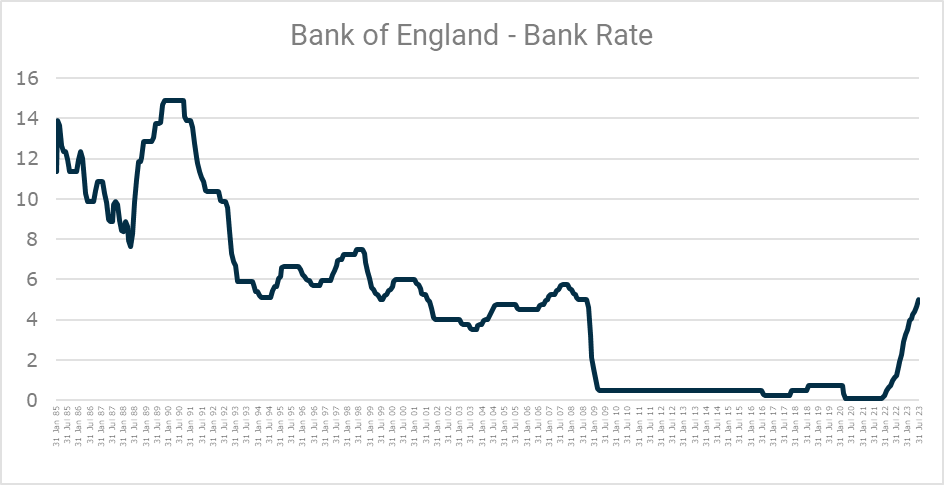

In December 2021 – just 20 months ago – the Bank rate was 0.1%; yesterday’s increase took that rate to 5.25%. Although the level of interest rates is not high by historical standards, the sharp transition is something we have not witnessed since the late 80s.

During the protracted period of low rates, corporates and households took on more debt and market participants searched for yield in higher-risk markets. Now, the worm has turned and it has done so quickly and in an extreme way. With Andrew Bailey stressing that the markets should expect the Bank to “keep this stance of policy”, we are likely to see high rates for some time.

We are helping our corporate clients to manage the transition – looking carefully at costs but also how they maintain agility. Corporates tend to rely on floating-rate loans, meaning that borrowing costs have already increased, reflecting the higher bank rate. This means their responses need to be swift and agile. The right advice is often to focus on core activities, defer investment decisions, and try to reduce their debt burden. All very sensible but, when done against a backdrop of shifting market dynamics, typically underpinned by a need to invest in technology, the increased cost of talent, and a much higher cost of doing business, this could become existential for some.

Unfortunately, some corporates will not make it through; they will become insolvent and need restructuring or enter liquidation. Some will say that Schumpeter’s gale of creative destruction is overdue and, as always, there will be winners and losers. The graphic below is reproduced from a recent paper from the FPC that considered the channels through which rising interest rates impact the financial system and the economy at large.

The FPC has pointed to the historic link between rising interest rates and corporate default. What is interesting from the graphic is the lag effect: although interest rates peaked at 14.875% for nearly a year from November 1989, insolvencies didn’t’ reach their peak until two years later.

For banks, expanding net interest margins have been good for profits over the last 18 months. However, with these benefits comes concern for the wider financial system.

Threats to the financial system

The increased probability that individuals and corporates will default on their debts is a risk for lenders, and we might expect to see banks taking losses through these defaults. The increased risk of default also means that banks need to set aside more capital against the same volume of loans and, as a result, credit conditions are likely to become tighter.

The UK economy has appeared resilient thus far, but the Bank will be mindful of lag effects and the risk of triggering a feedback loop through – tighter credit conditions – difficult refinancing – a high probability of default – tighter credit conditions.

The Financial Policy Committee of the Bank of England pointed to two further related risks to the financial system:

- a sharp fall in asset values; and, as a result;

- higher margin calls on derivative positions.

We have seen some evidence of the impact of these risks already as the financial system makes its transition to a higher-rate environment.

Failure of three mid-sized banks

One of the primary reasons behind the failure of SVB and First Republic was the concern over the banks’ ability to manage interest rate risk. As has been widely reported, a number of mid-size US banks held significant bond portfolios (including US Treasuries) – which sounds safe but the problem was that the fair value of these bonds was undermined by the sharp increase in rates. If the bank was forced to liquidate the bonds in the open market to meet deposit outflows, then there would not be enough cash to go round – panic, a classic bank run.

There is also a more direct impact of the fall in the fair value of assets in that many bonds are used as collateral for repo transactions. Borrowers in the repo market will need to lodge more collateral to support variation margin as the value of that collateral falls. More generally, ongoing uncertainty surrounding interest rates causes market volatility and this will also increase the amount of initial margin that market participants lodge to support derivative transactions, including interest rate swaps. Margin calls can drain liquidity from a financial institution rapidly, causing the liquidation of assets at price levels that are unattractive. Forced deleveraging of this nature was essentially the issue faced by the LDI funds last year, liquidating gilts into a falling market and adding weight to a downward spiral. The FPC at the Bank of England has also flagged the risk of spillover effects with broader market dysfunction leading to an unwanted tightening of credit conditions.

Concluding thoughts

Mr Bailey sits across both the MPC and the FPC. Although the “long, shallow recession” that had been forecast has not yet arrived, the lag effects between increasing rates and corporate defaults will be top of mind. We may well be approaching the top of the interest rate cycle, but if rates are held at this level for a protracted period of time we should expect to see more restructuring and, with it, stresses across the financial system. The Bank says that inflation will not return to the 2 per cent target until mid-2025 – there can be no guarantee that lending conditions will not be tighter by then than they are today. A deeper, protracted, recession remains a possibility.